"For

a Native American, a healing is a spiritual journey," declares

Lewis Mehl-Madrona, M.D., author of Coyote Medicine and a descendent

of the Lakota and Cherokee tribes. "What happens to the

body reflects what is happening in the mind and spirit."

The integration of the physical

and the spiritual is at the heart of the tradition of sweat

lodges, a Native American ceremony believed to be the most

widely practiced indigenous healing ritual. "For us, it's

sort of like going to church, something to practice on a regular

basis," says Mehl-Madrona, research

coordinator for the program of integrative medicine at the University

of Arizona in Tucson. A sweat can be used as its own ceremony,

to cleanse oneself and reconnect with Mother Earth, or as preparation

for other important undertakings, such as the Vision Quest or the

Sun Dance.

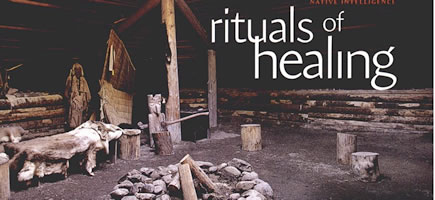

The sweat lodge

is a place of magic and visions, but it is also physically

taxing. Drink plenty of water on the day of a swat. Eat

lightly, wear loose, lightweight clothing.

| Herbs are often used in

ceremonies. At some sweat lodges, sage and cedar are

thought to purify the space (and the participants)

while tobacco leaves bless the earth. "Because

it's plentiful around here, I sometimes use eucalyptus.

too," says Edward Albert, whose backyeard sweat

lodge is a place for family to gather. |

The particulars of the rituals vary from

tribe to tribe and from family to family, says Mehl-Madrona.

Yet the central concept is always to purify body, mind and

soul through intense heat generated by pouring water over hot

rocks. Some form of this ancient practice is found in cultures

around the world, from the Finnish sauna to the Russian bania,

and from the Jewish shvitz to the Turkish hamman.

"You're essentially

generating a fever in the body," Mehl-Madrona explains.

The physical benefits of this have been enumerated in study

after study, he says. A body temperature of 102 to 106 degrees

("which is what we suspect is generated in a sweat lodge")

creates a hostile environment for bacterial and viral infection. Sweating flushes toxic metals,

such as copper, lead and mercury, and removes excess salt,

a benefit for those with mild hypertension. The heat and sweating

also helps ease soreness and stiffness, and dilates capillaries,

increasing blood flow to the skin. Mehl-Madrona participates

in sweat-lodge ceremonies with Native American patients and

others who feel they might benefit, but the physical rewards

are only one small reason. A sweat lodge can't be separated

from its context as a spiritual ritual or it loses its power. "If you just want to

feel better sweating, go take a sauna, but don't call it a

sweat," he insists. "Healing comes on a spiritual

level. We have to make ourselves available to the spiritual

realm. Ceremony and ritual provide the means of making ourselves

available." ceremony

and song Almost every aspect of a

sweat lodge has a symbolic meaning, says Edward Albert, the

California state commissioner for Native American lands. Lodges

are usually round or oval, reflecting the shape of the womb,

and the experience is likened to being reborn in healing energy.

The flap or door of a lodge is generally built very low, forcing

people to enter crouched or even on their knees as a show of

humility and respect for the earth as a sacred, living entity. Although construction varies,

numerous tribes prefer willow, which has long been used medicinally

(its bark contains salicin, the analgesic in aspirin compounds);

it's known as the "tree of love" in the Seneca tradition,

due to its resilience and grace. Since willow dies in the winter

and comes up again in spring, it also offers a lesson in death

and rebirth. Saplings are set up to represent

four quadrants, signifying the four elements and the four directions.

Originally, lodges were covered with animal skins; contemporary

structures use blankets or tarpaulins. A fire pit just outside

the lodge is used to heat rocks, called the Stone People, which

represent one's elders. When the rocks are thoroughly heated,

they are brought into the tent in a series of four rounds (or

sometimes 16 or 32 rounds). Then water is poured on the stones,

generating steam, which symbolizes, in part, the release of

ancient knowledge.

A sweat begins in total silence-sometimes

thought of as the "true voice of the Creator"-but

songs, prayers, chants and heartfelt talk are central to most

ceremonies. Sweats can last for days at a time in traditional

settings, but for the newly initiated a two-hour series of

rounds provides a complete experience.

Though generally considered

safe, says Mehl-Madrona, the excessive sweating produced in

a lodge isn't for everyone, because it can adversely interact

with medication or exacerbate certain conditions. Pregnant

women, people with heart disease, and anyone taking benzodiazepines

(Xanax, Valium) should check with their physicians before participating

in a sweat lodge ceremony.

Others who should proceed

with caution are very overweight and very underweight people,

who have an equally difficult time regulating body temperature

and are more likely to faint in excessive heat. And those who

suffer from claustrophobia and post-traumatic stress disorders

can have their conditions triggered by the dark, closed space

of a lodge.

|